New review just published by 'Music on the web' of the Bartok 2 Piano and Percussion Sonata, Stravinsky 'Rite of Spring' and Charles Camilleri 'Concerto for 2 Pianos and Percussion' disc (It can be found at www.musicwebinternational.com/

Herewith in its entirety:

www.dunelm-records.co.uk

Innovations: Music by Camilleri, Stravinsky and Bartok

Charles CAMILLERI (b. 1931) Concerto for Two Pianos and Percussion (2005) [20.59]

Igor STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) The Rite of Spring (1912-13 revised 1947) Reduction for piano duet by the composer. [34.18]

Bela BARTOK (1881-1945) Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937) [26.51]

Kathryn Page; Murray McLachlan (piano)

Heather Corbett; Stephen Burke (percussion)

rec. Whiteley Hall, Manchester, 1 Sept 2005, 28 Jan 2006. DDD Stereo

DUNELM RECORDS DRDO258. [2 CDs: 82.11]

From ever-enterprising Dunelm comes this interesting disc of works both new and old. The Stravinsky and Bartok pieces are classics, although the former’s The Rite of Spring is played here in the composer’s own arrangement for piano duet. The new work is Charles Camilleri’s Concerto for Two Pianos and Percussion which was written in part as a response to Bartok’s Sonata for the same combination of instruments.

Camilleri was born in Malta but is a cosmopolitan figure who has lived in London and New York. His work is not particularly well known in this country but it was as a result of his visit to Chetham’s School of Music Summer School, 2004 that the new concerto was written. It was Murray McLachlan who suggested to the composer the possibility of writing a piece that used the same forces as Bartok’s work. The resulting work is a colourful addition to what is a small repertoire for this type of ensemble. The composer has written that he wanted to explore the possibility of treating tonality, modality and atonality as equal partners. In so doing he has avoided the trap of diffusion and eclecticism. How he does this is by means of a subtle blending of the compositional elements. Modal fragments figure much in the slow central movement but they appear almost as folk memories amid the shifting harmonies that surround them. The tonal elements are often quickly subverted by dissonance; the harmonies remain mobile in a way that sometimes suggests Boulez, particularly in parts of the first movement. The percussion instruments are used both rhythmically and colouristically. The last movement is propelled by tambourine and snare drum in a way that recalls Lambert’s Rio Grande. This is a resourceful and enjoyable new work.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is so familiar in its orchestral form that I was initially sceptical about its chances of success as a piano duet. The CD booklet describes the version as a reduction so it is not clear whether the composer intended it to be performed as a concert piece or whether he had in mind the rehearsal needs of the corps de ballet and their preparations with a pair of pianistic répétiteurs. Whatever the reason this new recording is very welcome and actually highlights different aspects of the work when compared to the orchestral version. Despite its percussive nature the piano can’t quite match the brutality of Stravinsky’s orchestration. In The Augurs of Spring the piano is no match for the savage string chords and barking horns. What this version reveals is a remarkable clarity of harmony, as if this most colourful of scores was being subjected to a Brahmsian ‘black and white’ test. Time and time again I found myself stopping the recording to replay sections whose harmony seemed strangely new despite my having known the work for nearly forty years. Often I was convinced of the influence of Debussy, a composer whom I had not hitherto considered in relation to this work. Despite the reduction from more than a hundred players to just two, the concluding Sacrificial Dance is still thrilling and this is largely due to the performance which is superb throughout. Page and McLachlan have done a great service in allowing us to hear Stravinsky’s music afresh and I would recommend this version to anyone interested in one of the monuments of 20th century music.

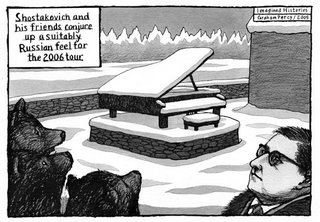

With Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion the performers tackle another masterpiece and they do so with aplomb. The work is also available in an expanded version for two pianos and orchestra but the original chamber version of 1938 is presented here. Eminent musicologist, Lendvai, has teased out some of Bartok’s structural devises used in works of this period such as symmetry, the Fibonacci sequence and the Golden Section – good for him! The overarching impression of the Sonata is not in fact that of a clever design but of a profound and chilling musical statement that received its first performance only two months before the Nazi Anschluss of Austria, an event that filled the composer with dismay. It is perhaps wrong to attach the work too closely to political events but there is something very sinister about the strange, loping chords and bursts of percussion with which the first movement begins. The performance on this disc is a fine one; I particularly enjoyed the reading of the mysterious slow movement with its dark, swirling colours and scurrying insects. The rhythmic finale carries the listener along with its energy and good spirits. When I hear the opening xylophone theme I am always reminded of Shostakovich, the composer Bartok was to lampoon a few years later in the Concerto for Orchestra.

This disc is very well served by the recording engineer; the pianos sound warm but clear and the percussion is bright – listen to the crackle of the suspended cymbal near the start of the Camilleri and the wash of vibraphone later in that work. All three works presented are valuable and the Camilleri concerto should now find a place in programmes that feature Bartok’s sonata. A thought provoking and rewarding issue.

David Hackbridge Johnson

Murray McLachlan: Breaking News